White Eared Kob (Kobuskobleucotis, Lichtenstein and Peters, 1854,) in Ethiopia; Migration Status, Potential Anthropogenic Threats and Conservation Directives from an Ecotourism Perspectives

Abstract

The Trans boundary protection of migratory species is a common argument for international cooperation. Ecotourism supports these activities through long-term commitment from international conservation organizations, all interest groups and various political entities. However, due to anthropogenic influences and inadequate understanding of species ecology, sustainable conservation of migratory species is often challenging. Therefore, this review article evaluates the migration status, potential anthropogenic threats, and conservation directives from the perspective of ecotourism of the white-eared kob (Kobuskobleucotis, Lichtenstein and Peters, 1854). Ethiopia. Kobus kobleucotis migrate through the Boma-Gambella border ecosystems of Ethiopia and South Sudan at certain times of the year. This migration is anonymous and requires an understanding of the overall ecology of the species. Currently, the white-eared Kob population exceeds half a million, making it the second largest migration in Africa, after the wildebeest migration in the Serengeti, Tanzania. Kobs occur in groups of five to forty depending on sex and age and are nocturnal but inactive on the hottest days. Rich grasslands and permanent water sources are the preferred habitats for the species. However, the decline in grassland potential, frequent hunting, expanding settlements, changes in land use and land cover are potential threats to the white-eared kob in Gambella National Parks. Therefore, understanding the total ecological, anthropogenic and behavioral variables that influence the movement and status of the species is the ultimate parameter for conservation activity. Furthermore, entire migration corridors require sustainable management by balancing stakeholder interests and rural community development through nature-based tourism. It is also noted that solid economic and environmental incentives through nature-based tourism require adequate protection in Gambella and the surrounding regions.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Andreia Manuela Garcês, University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro.

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2024 Atinafa Sahile

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

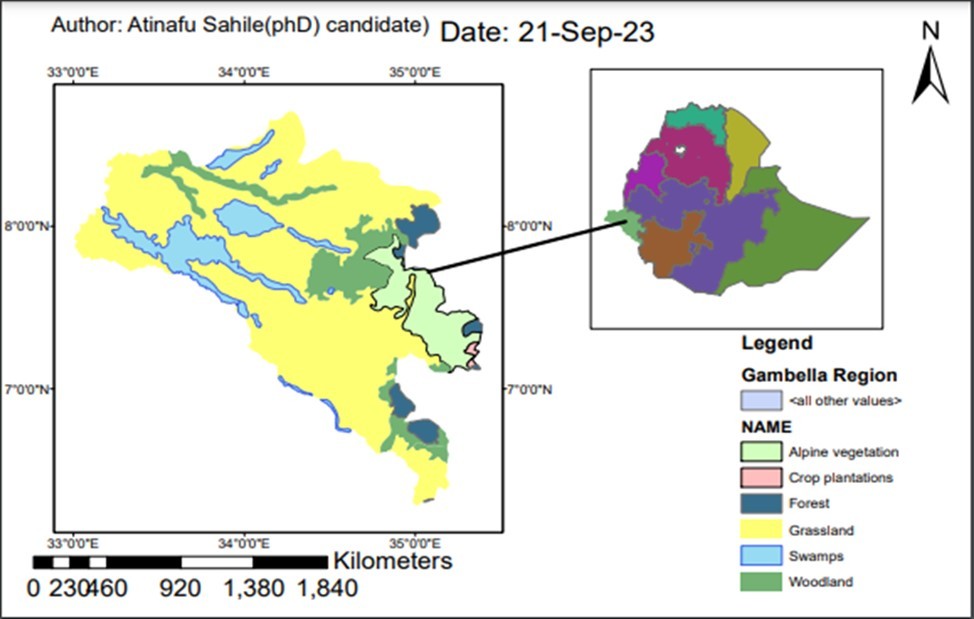

Protecting migratory species requires international cooperation to protect biodiversity. Therefore, participatory conservation approaches enable sustainable ecosystem protection for migratory species (Larsen et al., 2020). The expansion of ecotourism supports these activities by generating billions of dollars (Horns and Ekerciolu 2018). Global environmental organizations have also made a long-term commitment to promoting these activities 30. In this regard, all stakeholders and international organizations must be involved for Tran’s border protection to be effective 47. Migratory species are currently being scrutinized more closely to protect them in the face of environmental changes at various levels (Mattsson et al., 2022).However, conservationists face the difficulty of understanding the ecology of these species and the peculiarities of their migration (Wilcove & Wikelski, 2008). The impacts on the habitat of a migratory species in a particular region could impact the benefits enjoyed by people in other regions due to different potential threats (Lopez-Hoffman et al., 2017). In eastern and southern Africa, declines in the number and spatial range of ungulate populations have been associated with land use change and loss of connectivity (Morrison et al., 2016). In Ethiopia, Kobus kobleucotis was most recently added to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and given the status of Migratory Ungulate of Least Concern (Group, 2016). This is due to the growing human and livestock populations in Ethiopia's special ecosystems (Fashing et al., 2022). Although wildlife tourism has become the most promising future economy with extensive regional ecotourism activities in the country (Geda, 2021), the migration routes of a large number of animal species have changed. Due to the lack of proper infrastructure and lack of promotion of the pasrk, tourism flow was low 7. Nevertheless, a limited study has been conducted to identify factors hindering the development of the tourism industry in the region 20. The majority of the Ethiopian Gambella with high migration potential between South Sudan and Ethiopia faces major challenges due to anthropogenic influences (Naidoo et al., 2016). On the other hand, current knowledge of partial migration in ungulates is sometimes limited by their size, long life, and extensive habitat use, requiring long-term studies and generalizations across spatial scales (Berg et al., 2019). Even if Ethiopia diversifies its possible potential revenue sources from ecotourism, the country faces challenges in generating the necessary economic benefits through nature-based tourism due to the high need for vast protected areas and a high level of ecological knowledge 44. The country is also a member of the Convention on Migratory Species (1979), but has been unable to map the movements of ungulates due to a lack of tracking data, necessitating the development of specific strategies to protect the movements and obtain the required economic and environmental benefits (Kauffman et al., 2021). Consequently, initiatives related to wildlife tourism and conservation still receive relatively little attention 9. Therefore the conceptual focus of this review article is limited to the migration status, potential anthropogenic threats and conservation directives from an ecotourism perspective for the white-eared kob (kobuskobleucotis, Lichtenstein and Peters, 1854) in Ethiopia, particularly in the Gambella Tran border area. the Gambella landscape is an isolated ecosystem on the border between two sovereign states, South Sudan and Ethiopia42. Figure 1

Figure 1.Map of Gambella regional state (by Author.2023)

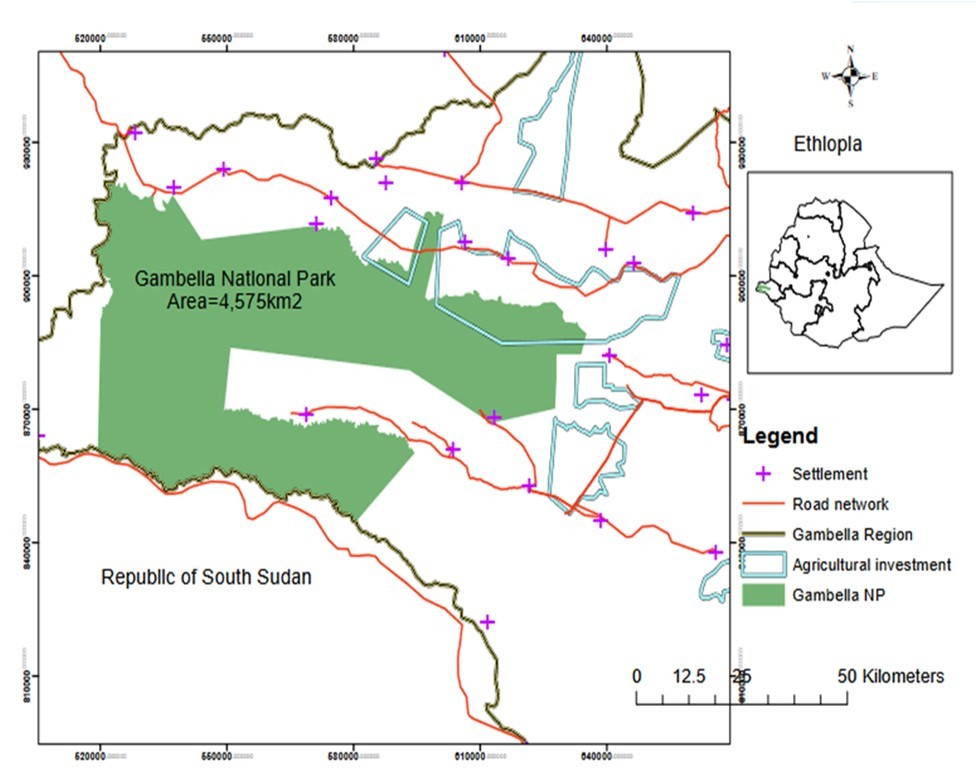

Gambella National Park is located at the central coordinates (34 0.00 E and 7 52.00 N) and 840 km west of Addis Ababa and covers a total area of 5061 km2 with an average elevation of about 550 m above sea level in Ethiopia 9. The park was established to protect extensive swampy habitats along the Akobo River with its wildlife and to protect two species of endangered wetland antelope: the white-eared kob and the Nile lechwe (Sheila, 2023). The vegetation type in Gambella National Park consists of shrub lands, floodplains, forests and long savanna grass forests 10. About 69 species of mammals are protected in the park, including predators such as lions, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas, etc. 6. The annual mean temperature is 18.09 °C and 39.34 °C with a minimum and maximum. The lowest rainfall is recorded from November to April, while the highest rainfall is recorded from May to October. Annual rainfall is estimated to be about 69.7 mm in the plains 11. Figure 2

Figure 2.Location of Gambella National Park within Gambella Peoples National Regional State ((Rolkier, 2021)

Migration status of white-eared kob

Migratory species regularly cross one or more national geographical boundaries, creating a geographically distinct part of each species population (Trouwborst, 2012). Every year, the white-eared kobus (Kobus kob leucotis) migrates across the Boma Gambella Tran borderland in Ethiopia in its largest seasonal migration (Nhial, 2019). As reported by Naidoo et al. (2016), migration is a continuous behavior rather than a variable response to environmental changes. Ungulates move regularly in highly seasonal environments (Mysterud et al., 2011). Migration in a temperate ecosystem refers to movement between high-elevation breeding grounds in summer and lowland areas with less snow in winter (Mysterud et al., 2011). Seasonal fluctuations in the availability of food, water, or both trigger migration in savannah ecosystems (Fryxell and Sinclair, 1988a). Large herbivores in Africa travel to locations with large spatiotemporal variation (Owen Smith et al., 2020). Migratory herbivores require more rainfall for their diet and soil fertility influences the quality of their forage (Owen-Smith et al., 2020). In East Africa, forage availability and quality influences significant movements of ungulates in many grassland ecosystems (Nhial, 2019). The migration of the white-eared kobus kob leucotis through the Boma Gambela ecosystems between South Sudan and Ethiopia is one of the most remarkable but understudied ungulate migrations 40. Kobus kob leucotis is a medium-sized antelope that lives mainly in wetlands with delicious green meadows in the GNP (Nhial, 2019). Males have a slightly yellowish-brown tint, while females have reddish or yellowish-orange cheeks and ears. Based on 11 and 39, the landscape of the GNP is low and flat with a high potential for grasslands and savanna grasslands, making it ideal for the species. The region is considered an excellent location and habitat for the white-eared kob (Kobus kob leucotis) due to preferred supply and potential wetland resources 39. The white-eared kob prefers low-rainfall grasslands in southern BSP during the rainy season because they are rich in nutrients and less susceptible to surface flooding (Fryxell and Sinclair, 1988a). Several hundred Kobus kob leucotis migrate from the floodplains of Sudd and Bandingilo National Parks in South Sudan to Gambella National Park in Ethiopia between January and June each year 24. Accordingly, Teitelbaum et al. (2015) recognized that there is a significant difference in migration distances within and between animals. In terms of migration distance, the migration of Burchell's zebra (Equus) was considered the longest migration of large animals. The white-eared kobus migration is the second largest in Africa after the Serengeti wildebeest migration in Tanzania 9. The migration occurs between January and June each year through the Boma Gambella ecosystem between Ethiopia and South Sudan 24.

In South Sudan, Kob migration routes typically avoid local human settlements, with the exception of short-term pastures for livestock 35. Its activity is influenced by anthropogenic factors such as urbanization, settlement expansion and rapidly growing refugee camps adjacent to Gambella National Park in Ethiopia (Waterville, 2015). Consistent with this, Kauffman et al. (2021) found that landscapes around the world are changing rapidly and that ungulates living alongside humans are highly vulnerable to changes in land use that affect their ability to migrate. Similarly, grasslands in BSP dry out during the high temperature season, and then white-eared kobus lose their food and are dispersed after moving to Boma National Park in South Sudan 11.

According to 23, management of migration corridors serves as temporary areas where animals can find food during migration, as well as sustainable routes for species to move within their seasonal ranges. On the other hand, future genetic research on the species of the genus Kobus should be aimed at natural populations in Africa for better management and conservation 35.

The spatiotemporal distribution of food availability along migration routes influences animal movements during migration (Aikens et al., 2017). Similarly, the migration routes and home ranges of the white-eared kobus have been found to overlap with hotspots of armed conflict and livestock areas in the Gambela landscape 3. Although migration has a distinct pattern of movement season, behavior and external factors, the white-eared kob (Kobuskobleucotis, Lichtenstein & Peters, 1853) is documented in Omo National Park and shows that its range extends further into Omo than previously known(Asfaw et al., 2022). Table1

Table1. Recent literatures about Migration status of white-eared kob (source; Google scholar and research get)| No | Title, author name and area of study | Migration status |

| 1 | Population Estimate,FeedingEcologyandHabitatCompetitionUseofWhite-EaredKob(KobusKobLeucotis,Lichtenstein,and Peters, 1854) and TheirInteraction with Livestock inGambellaNationalPark,SouthwesternEthiopiaNhial, T. (2019). | Ethiopia is known among the East African countries hosting one of the few remaining sites in Africa where significant seasonal migration still occurs at Boma– Gambella Trans boundary Park for white – eared kob (Kobus kob leucotis). |

| 2 | ‘Wildlife migration in Ethiopia and South Sudan longer than 'the longest in Africa 40 | White eared Kob fitted with Satellite collars for preliminary survey results indicate that one individual migrated a round-trip distance of 825 km which may be taken as a proxy for the migration of several large herds. |

| 3 | Fryxell, JM, and Sinclair,A.R.E. (1988a) 'Seasonal migration by white-eared kob about resources', AfricanJournalofEcology, 26(1), pp. 17–31. | A migratory population of over 800,000 white-eared kob in Boma National Park of south Sudan Move into the dry season range in the northern part of the ecosystem was correlated with seasonally scarce supplies of both food and water. In the dry season range, kob concentrated atdensities often exceeding 1000 km-2 in low-lying meadows |

| 4 | ‘Filming the White Eared Kobs in Ethiopia - 24. | The white-eared kob is the animal that dominates the world‟s second largest great wildlife migration which takes place between South Sudan and Ethiopia, this happens every year from January to June where animals move in masses from the floodplains of the Sudd and Bandingilo National Park across to Boma National Park and into Gambella National Park in Ethiopia. Best areas to film thewhite-eared kob include Sudd Swamp, Bandingilo National Park, Boma National Park and Gambelle National Park in Ethiopia. |

| 5 | Wildlife Resources of Ethiopia: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions from Ecotourism Perspective (Amare, A. 2015a) | A large migratory population of White-eared kob migrates to and from Boma National Park in South Sudan, neighboring country of Ethiopia. Approximately, more than half million population of animals migrates and ranked the second migration in Africa next to the Serengeti Wildebeest migration in Tanzania. |

| 6 | Armed conflict and development in South Sudan threaten some of the longest and largest ungulate migrations in Africa 37 | The annual movements of white-eared kob (Kobuskobleucotis), tiang (Damaliscuskorrigumtiang), in eastern South Sudan was investigated to provided appropriate information for developing effective conservation actions for the migratory kob. |

| 7 | ‘First record of White-eared Kob ( Kobuskobleucotis) in Omo National Park, Ethiopia (Artiodactyla, Bovidae 12’ | White-eared Kob, Kobus kob leucotis, Lichtenstein & Peters, 1853, is known to occur in the Gambela-Boma landscape in western Ethiopia and South Sudan. However, the first documentation were recorded in Omo National Park and showing that its range extends further to Omothan previously known |

Potential anthropogenic threats to white-eared kob

Migratory ungulates are threatened worldwide 17. A significant risk to migratory mammals is direct human-caused mortality of wildlife in many protected areas in Ethiopia 12 (Bunn, 2019; Legas and Taye, 2019; Shibru et al., 2020). According to 12, 2 and Ahmedin (2000), inadequate environmental education, lack of community participation, unfair revenue sharing system and lack of comprehensive conservation strategies contribute to the risks at. Therefore, a number of researchers have identified the following threats in the habitats and migration routes of the white-eared kobus.

Hunting

Many migrations are affected by overhunting 30 and the level of hunting is more directly related to the number of wild animals in natural ecosystems 27. Similarly, bush meat collection poses a significant threat to the management of Gambella National Park, particularly to the white-eared cob species (Legas and Taye, 2019). It was previously thought that there was only a small population of food-producing hunters in the area 28.

Both refugees and some military personnel in Gambella Regional State have had a negative impact on the park's wildlife resources. The type of hunting in the region is also changing to automatic weapons 11. The traditional methods of wildlife hunting, such as setting traps and snares, are no longer sustainable as the reasons for hunting in the region are largely shifting from subsistence to commercial hunting 45. In this scenario 26, it was noted that the tragic reality of conflict within biodiversity hotspots requires a better understanding of the complex dynamics affecting wildlife and ecosystems. Figure 3

Figure 3.White-eared kob bush meat collected through hunting (Source: By Author, 2023)

Change in land use and land cover

Formal approaches to wildlife conservation in Ethiopia followed a similar pattern to other countries in Anglophone Africa, where extensive networks of generally exclusive protected areas were established 43. However, Ethiopia's protected areas are facing increasing threats and changes in land cover due to population growth, competing claims of surrounding communities, incompatible investments, lack of environmental legislation, lack of complete plans and timely updates for protected areas, etc. (Menbere., 2021). The Ethiopian government promotes large-scale agricultural investments in lowland regions of the country, so large-scale commercial agricultural programs have been the main driver of land use/cover change in Ethiopia 36. Likewise, agricultural investments in the Gambella region have led to a reduction in the previous national park area from 5,06 km2 to 4,575 km225. On the other hand, refugee camps continue to increase along the migration route, causing agricultural production to be an important anthropogenic factor that alters the E-Eared Kob migration route (Waterville, 2015). Furthermore, the percentage area changes in the Gambella region between 2000 and 2017 showed those most tropical grasslands of the LU/LC class declined by 50% 16. The conversion of savanna/tropical grasslands into agricultural cropland has resulted in diverse and widespread environmental damage.

In most parts of Ethiopia, particularly in the Gambella region, the failure to consider “rural land rights” was identified as a core problem, leading to competition for land use rights between small farmers and all state institutions associated with the socio-economic expansion Coping with disruptions and developing LSAI in Ethiopia 5. The results of LSAI have been a controversial topic in public and hypothetical discourses, especially regarding the quantification of the impact of such investments on natural resources 29. On the other hand, a rapidly growing human population and the prospect of oil exploration threaten the Kobus kob leucotis in South Sudan, potentially putting the available corridor for white-eared kob in both countries at risk 37.

Armed conflicts have occurred throughout the species' migration and feeding sites. This explains why migration remains poorly understood and increases the threat to the extreme 40. Forced relocations in villages bordering Gambella National Park also led to degradation of the species' important habitats and foraging areas 1. The communities of these villages used to clear grassland and trees to build their houses and participated in hunting 1. Consistent with this 38, they found that distances from settlements and water resulted in noticeable spatial segregation between species in the location of their points of maximum density, presumably to minimize interspecific competition for food and water.

The complete degradation of wetlands, the creation of a new landscape, conflicts of interest due to resource scarcity and the reduction of forested land cover have placed severe pressure on the survival of the white-eared kob in the Gambella region 2, 36, 5. However, sustainable tourism maximizes the benefits and minimizes its negative impacts through effective policies and plans for great progress in the future 48. Furthermore, international contributions are crucial, but ultimate sustainable success depends on the daily commitment and efforts of those at the local level who must interact 47. Figure 4

Figure 4.White-eared kobs during peak fire season in Gambella National Park (Kassahun Abera, 2018).

Conservation directives on (Kobus kob leucotis) from Ecotourism perspectives

There is tourism potential in the Gambella region. However, it is still at an early stage of developing its tourism sector. Gambelle National Park and surrounding areas in Ethiopia are the best places to photograph white-eared cobs 24. According to 4, the landscape is interconnected through ecosystems, cultures and shared cultural and ecological characteristics. These factors provide opportunities to promote coordinated development, peace and security. The protection of iconic species is significantly supported by the adaptation and application of tourism marketing for national parks and sustainable tourism 8. To be effective, a practical assessment, feasibility, cost-effectiveness analysis, social impact analysis and sustainability for each individual site are the most critical solutions 32. Additionally, because many terrestrial animal migrations disappear before they can be fully documented, a fundamental analysis of the movement patterns of large mammalian herbivores is critical 37. Since the migration area often spans multiple political organizations, intergovernmental cooperation is an essential but often challenging aspect of migration protection (Horns and Ekerciolu, 2018). Therefore, properly managed ecotourism can result in an overall positive change in the expected survival of endangered species such as Kobus kob leucotis 15. The health and persistence of large game herds and the resulting positive economic impacts rely largely on the effective management of seasonal ranges and movement routes or “migration corridors” 23. However, conservation of migratory species can be problematic due to their need for large protected areas 44.

Ecotourism offers a win-win approach to contribute a net positive effect on both the conservation of the natural ecosystem and the livelihoods of communities 14. Ethiopia promotes the tourism industry in Ethiopia due to its large mammal diversity and scenic area, expansion of protected areas, peaceful and friendly people and endemism 10. To strengthen the feasibility of self-financing PAs while protecting its iconic migratory species, Ethiopia needs to expand its ecotourism business 14. This can be achieved by expanding the application of adaptive management concepts and improving local community participation in ecotourism decision-making (Cheung, 2015). The country needs to promote sustainable tourism, including ecotourism, based on the principles of sustainability – social justice, economic efficiency and environmental sustainability 48. On the other hand, successful conservation measures require in-depth knowledge of the ecology of the population and the migratory behavior of the species and are crucial for sound conservation 44. In this context, the Gambella region is also referred to as a desert paradise due to its attractive tourism potential 20. Wildlife tourism has positively contributed to providing diverse employment opportunities to the community, primarily through the integration of cultural and natural resources into the region's wilderness experience 34. Therefore, offering tourism facilities and services and creating employment opportunities for members of local communities are the positive impacts of tourism activities 19. However, tourism does not currently address other major conservation threats associated with natural resource extraction industries 15. Modest changes can have significant impacts, such as maintaining a small area of habitat that serves as an important migration corridor or buffer zone; Ecotourism could provide the necessary incentive 32. Table 2

Table 2. Potential anthropogenic threats to white-eared kob (source; Google scholar and research get)| Hunting as an anthropogenic threats | ||||

| No | Title, author name and area of study | Discretion | ||

| 1 | Legas, M.S. and Taye, B. (2019), Impacts of human activities on wildlife: The case of Gambella National Park southwest Ethiopia | Most of residents in Gambella region used hunting as a primary and secondary professional activity across Boma-Gambela landscape. | ||

| 2 | 28„Late hunters of western Ethiopia: the sites of Ajilak (Gambela), c. AD 1000–1200 | The exploitation of aquatic resources is also attested. Human remains were found that show traces of manipulation, tentatively identified as evidence for the practice of secondary burial. The sites are interpreted as being related to a low-level food-producing group that was probably ancestral to present-day populations engaging in similar economic activities. | ||

| 3 | 25 „Management Challenges of Gambella National Park | The traditional method of hunting by local community changed To hunting with automatic weapons they purchased from the SPLA soldiers. The local population had got army ammunition from the SPLA and therefore, both the local communities of Gambella and SPLA soldiers were heavily engaged in Poaching. | ||

| Change in land use and land cover as an anthropogenic threats | ||||

| 1 | 25 „Management Challenges ofGambella National Park | There was increasing deforestation in the areas around all refugee camps where the refugees cleared the woodland for house construction and firewood. | ||

| 2 | 16„Assessing land use and land cover changes and agricultural farmland expansions in Gambella Region, Ethiopia, | Gambella National Park, which is the nation‟s largest national park and ecosystem, Was also largely affected by Land Use and Land Cover changes? The conversion of savannah/tropical grasslands to agricultural farmland has caused varied and extensive environmental degradation to the parkGambella National Park, which is the nation’s largest national park and ecosystem, Was also largely affected by Land Use and Land Cover changes. The conversion of savannah/tropical grasslands to agricultural farmland has caused varied and extensive environmental degradation to the park Gambella National Park, which is the nation’s largest national park and ecosystem, Was also largely affected by Land Use and Land Cover changes? The conversion of savannah/tropical grasslands to agricultural farmland has caused varied and extensive environmental degradation to the park Gambella National Park, which is the nation’s largest national park and ecosystem, Was also largely affected by Land Use and Land Cover changes? The conversion ofsavannah/tropical grasslands to agricultural farmland has caused varied andextensive environmental degradation to the park | ||

| 3 | 37 „Armed conflict and development in South Sudan threatens some of Africa‟s longest and largest ungulate migrations‟ | The kob range was 68,805 km2, 29% of which was within national parks and 72% within leased oil concessions (54–83% of parks overlap with potential oil concessions). Because disruption or elimination of these migrations will inevitably lead to significant population reductions, | ||

For threatened species that are well represented in existing but underfunded protected areas, appropriately managed ecotourism can result in a net gain in expected survival overall 15. To achieve sustainable wildlife management and rural community development around Gambella National Parks, stakeholders' interests must be aligned 33. This strengthens the suggestion that the sustainability of conservation projects depends on the involvement of all stakeholders and the development of a supportive constituency. While international organizations play a critical role in educating, equipping, and facilitating Tran’s boundary conservation, they cannot enforce it 47. “Major research needs are to collect and analyze data on ungulate movements to refine the delineation of winter ranges, summer ranges and migration corridors and to support a better understanding of how ungulates use these habitats 18,” research efforts to measure such key population parameters Identifying additional threatened species and quantifying the various impacts of ecotourism on these parameters is now a priority as ecotourism is increasingly advocated as a conservation tool 15.

Appropriate environmentally friendly management needs to be developed with options to mitigate impacts and minimize future impacts 33. Community-based ecotourism ensures the involvement of local communities from the grassroots to improve their living standards 13. In addition to development activities, any development practice should also consider and take into account the rapidly diminishing natural resources 41. Securing seasonal ranges, resource protection, and government support is the most urgent conservation measure for many ungulate migrations that require attention 30. In this scenario, improving infrastructure (roads, accommodation providers, campsites, water supply, internet cafes, telecommunications, banking services and electricity) is crucial for the tourism destinations with the involvement of multiple stakeholders 21. The ongoing conflicts and sustainable symbiosis between ecotourism and conservation require urgent policy interventions, especially to integrate the principles and practices of ecotourism into the neoliberal approach to conservation 14.

Conclusions

Because migration corridors provide a reliable route between their seasonal home ranges, ungulates migrate in response to seasonal fluctuations in food availability. The migration of the white-eared kob (Kobus kob leucotis) is one of the most spectacular but least studied mass migrations in Africa. It occurs in the Boma-Gambela landscape, which lies on the border between South Sudan and Ethiopia. Aside from the Serengeti wildebeest migration in Tanzania, the migration of about 500,000 Kobs is the largest migration in Africa and occurs between Ethiopia and South Sudan. White-eared cob population movements were influenced by the quantity and quality of forage, leading to large-scale migrations in many other grassland ecosystems in East Africa. The population status of the Gambella region is heavily influenced by anthropogenic threats such as hunting, habitat loss, agricultural expansion and indirect causes such as ongoing ethnic conflicts within and outside the Trans border. Because it is still unknown why these animals migrate, conservation of white-eared cobs is the most difficult problem facing the vast majority of the Gambella Boma Tran frontier ecosystem. Many researchers continue to believe that this migration is caused by seasonal fluctuations in the distribution of food and water, or both. Although migration is not a response to environmental events; rather, it is a constant behavior. The reasons for such long-distance migration remain a mystery. To provide sound economic and environmental incentives to this migratory species through nature-based tourism, a sufficient understanding of the general ecological, anthropogenic and behavioral variables that influence the species' migration is essential. to ensure comprehensive protection and conservation measure, Extensive studies on ecology, migration dynamics and other factors influencing species are important to propose and implement conservation strategies and habitat mapping. The adoption and effective recognition of the concept of ecotourism is also the most important strategies to promote the potential ecological and economic value of species.

List of Abbreviation

GNP- Gambella national Park

IUCN- International Union of Nature Conservation

LSAI - large-scale Agricultural investment

M a, s.l- Meter above sea level

PA- Protected Area

References

- 2.F B Abebe, S E Bekele. (2018) Challenges to national park conservation and management in Ethiopia‟. , Journal of Agricultural Science 10(5), 52.

- 3.Abera K, Bekele A. (2018) Analyzing the effect of armed conflict, agriculture, and fire on the movement and migratory behavior of white-eared kob and Roan antelope in the Boma-Gambella landscape of Ethiopia and South Sudan. , Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena

- 4.Abera K, Bekele A. (2018) Analyzing the effect of armed conflict, agriculture, and fire on the movement and migratory behavior of white-eared kob and Roan antelope in the Boma-Gambella landscape of Ethiopia and South Sudan. , Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena

- 5.Abesha N, Assefa E, M A Petrova. (2022) Large-scale agricultural investment in Ethiopia: Development, challenges and policy responses‟. , Land Use Policy 117, 106091.

- 6. (2023) ACF (2012a) „Ethiopia: Number of Wild Animals On Rise. in Gambella National Park‟, African ConservationFoundation,17April.Availableat:https://africanconservation.org/ethiopia-number-of-wild-animals-on-rise-in-gambella- national-park-2/ (Accessed: 13 .

- 7. (2023) ACF (2012b) „Ethiopia: Number of Wild Animals On Rise. in Gambella National Park‟, African ConservationFoundation,17April.Availableat:https:/africanconservation.org/ethiopia-number-of-wild-animals-on-rise-in-gambella-national-park-2/ (Accessed: 8 .

- 8.Aman E, Á F Papp-Váry. (2023) Sustainability of National Park and Tourism Development: -A systematic review on Bale Mountain National Park. , Ethiopia‟, in

- 9.Amare A. (2015) Wildlife Resources of Ethiopia: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions: From Ecotourism Perspective: A Review Paper‟. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4236/nr.2015.66039 , Natural Resources 06(06), 405-422.

- 10.Amare A.(2015b) 'Wildlife resources of Ethiopia: Opportunities, challenges, and future directions: From ecotourism perspective: A review paper‟. , Natural Resources 6(06), 405.

- 11.A B. (2016) Vegetation composition and deforestation impact in Gambella National Park, Ethiopia‟. , Journal of Energy and Natural Resources 5(3), 30-36.

- 12.Asefa A, Mengesha G, Aychew M. (2017) Direct human-caused wildlife mortalities in Geralle National Park, southern Ethiopia: implications for conservation‟, SINET:. , Ethiopian Journal of Science 40(1), 42-45.

- 13.S A Aseres. (2015) Potentialities of community participation in community-based ecotourism development: Perspective of sustainable local development a case of Choke Mountain. , Northern Ethiopia‟, J. Hotel Bus. Manag 4, 1-4.

- 14.S A Aseres, R K Sira. (2020) Ecotourism development in Ethiopia: costs and benefits for protected area conservation‟. , Journal of Ecotourism [Preprint]. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14724049.2020.1857390 (Accessed: 11.

- 15.R C Buckley, Morrison C, J G Castley. (2016) . Net Effects of Ecotourism on Threatened Species Survival‟, PLOS ONE Available at:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147988 11(2), 0147988.

- 16.A W Degife, Zabel F, Mauser W. (2018) Assessing land use and land cover changes and agricultural farmland expansions. in Gambella Region, Ethiopia, using Landsat 5 and Sentinel 2a multispectral data‟, Heliyon, 4(11). Available at:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00919 .

- 17.C L Dybas.(2022a) „Born to Roam: Tracking the Drama of Earth‟s Ungulate. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biac096 , Migrations‟, BioScience 72(12), 1141-1148.

- 18.C L Dybas.(2022b) „Born to Roam: Tracking the Drama of Earth‟s Ungulate. , Migrations‟, BioScience 72(12), 1141-1148.

- 19.S M Ertiban, Maru B. (2020) Wildlife and Ecotourism Contributions for Sustainable Natural Resource Management. In and Around Bale Mountains National Park, Southeastern Ethiopia. preprint. In Review. Available at:https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-15479/v2 .

- 20.Fakana S, Alemken, Mengist A. (2019) Factors Hindering Tourism Industry Development: Gambella People‟s National Regional State. , South West Ethiopia‟

- 21.S T Fakana, A B Mengist.(2019a) „Opportunities to Enhance Tourism Industry Development: Gambella People‟s National Regional State, South West Ethiopia‟. Available at:https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijhtm.20190302.11 , International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management 3(2), 18.

- 22.S T Fakana, A B Mengist.(2019b) „Unexplored Natural Tourism Potentials: Gambella Peo- ple‟s National Regional State, South West Ethiopia‟. Available at:https://doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.9.05.2019.p8940 , International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications (IJSRP) 9(5), 8940.

- 23.Feeney D. University of Wyoming (2004) Big game migration corridors in Wyoming‟. Cooperative Extension Service Bulletin B-1155 , Laramie, WY [Preprint] .

- 24. (2020) Filming the White Eared Kobs in Ethiopia - Film Crew Fixers‟. Available at: https://film-fixers.com/filming-the-white-eared-kobs-in-ethiopia/, https://film- fixers.com/filming-the-white-eared-kobs-in-ethiopia/ (Accessed: 12.

- 25.Rolkier Gatkoth, G, Ruot M. (2023) . Management Challenges of Gambella National Park‟, inEnvironmentalSciences.IntechOpen.Availableat:https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.109552 .

- 26.K M Gaynor. (2016) War, and wildlife: linking armed conflict to conservation'. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14(10), 533-542.

- 27.Getachew M, Nigatu L. (2022) Traditional Hunting Associated Oral Literature and its Environmental Impacts in Southwestern Ethiopia‟. , The Ethiopian Journal of Social Sciences and Language Studies (EJSSLS) 9(2), 57-71.

- 28.González-Ruibal A. (2014) Late hunters of western Ethiopia: the sites of Ajilak (Gambela). c. AD 1000–1200‟, Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa [Preprint]. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0067270X.2013.866843 (Accessed: 26 .

- 29.A K Guyalo, E A Alemu, D T. (2021) Impact of large-scale agricultural investment on the livelihood assets of the local community in Gambella region. , Ethiopia', International Journal of Social Economics 48(3), 363-383.

- 30.Harris G. (2009) Global decline in aggregated migrations of large terrestrial mammals‟. , Endangered Species Research 7(1), 55-76.

- 31. (2015) Human-Wildlife Conflict along the Transboundary Migration of White-Eared Kob in and around Gambella and Boma National Parks'. edu … , Waterville, Maine, USA: Colby College. https://web. colby

- 32.Kiss A. (2004) Is community-based ecotourism a good use of biodiversity conservation funds?‟. , Trends in ecology & evolution 19(5), 232-237.

- 33.M S Legas, B T Mamo. (2018) Impact of human activities on wildlife: the case of Nile Lechwe in Gambella National Park Southwest Ethiopia.‟. , International Journal of Conservation Science 9(4).

- 34.R J Lekgau, T M. (2020) Leveraging Wildlife Tourism for Employment Generation and Sustainable Livelihoods: The Case of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park. , Southern, Africa‟, Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series 49(49), 93-108.

- 35.Marjan. (2014) Movements and Conservation of the Migratory white-eared kob (Kobus kob leucotis) in South Sudan‟.

- 36.Mathewos M. (2019) Reported driving factors of land-use/cover changes and its mounting consequences in Ethiopia: A Review‟. Available at:https://doi.org/10.5897/AJEST2019.2680 , African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 13(7), 273-280.

- 37.Morjan. (2018) Armed conflict and development in South Sudan threatens some of Africa‟s longest and largest ungulate migrations‟. , Biodiversity and Conservation 27(2), 365-380.

- 38.J O Ogutu. (2010) Large herbivore responses to water and settlements in savannas‟. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1890/09- , Ecological Monographs 80(2), 241-266.

- 39.Rolkier G, Yeshitela K. (2020) Vegetation Classification and Habitat Types of Gambella National Park‟. Available at:https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8612593 , International Journal of Forestry Research

- 40.Schapira P. (2017) Wildlife migration in Ethiopia and South Sudan longer than “the longest in Africa”: a response to Naidoo et al.‟. Available at:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605316000363 , Oryx 51(1), pp..

- 41.Seid M, Taye B. (2018) Public attitude and prospective factors of wildlife conservation the case of Gambella National Park, Southwest Ethiopia'. Available at:https://doi.org/10.22192/ijarsbs.2018.05.10.012.

- 42.Debessa Sori, T. (2021) . , TRANS-BOUNDARY ECOSYSTEM CONSERVATION AND ITS CHALLENGES: THE CASE OF GAMBELLA-BOMA-BANDINGILO CORRIDOR. PhD Thesis

- 43.M E Tessema. (2010) Community Attitudes Toward Wildlife and Protected Areas in. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920903177867 , Ethiopia‟, Society & Natural Resources 23(6), 489-506.

- 44.Thirgood S. (2004) Can parks protect migratory ungulates? The case of the Serengeti wildebeest‟. Available at:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1367943004001404 , Animal Conservation 7(2), 113-120.

- 45.Y A Wato, G M Wahungu, M. (2006) Correlates of wildlife snaring patterns in Tsavo West National Park, Kenya'. , Biological conservation 132(4), 500-509.

- 46. (2023) White-eared Kob Migration in Gambela National Park, Ethiopia - Travels With Sheila (no date). Available at: https://travelswithsheila.com/gambela-national-park-ethiopia.html (Accessed: 5.